Advanced ggplot2: Watermarks and Overlays

Hi Readers,

Previously I mentioned I’m working on a contract for the Newfoundland government. For this contract I’ve had to make a number of figures for a report that’s coming out in the near future on the state of Caribou in the province. When I began the contract I was new to ggplot2, a nice graphics package by R guru Hadley Wickham which has become de rigueur in the circles I find myself in. Now I use it all the time when I want to make high quality figures.

For its many virtues there are drawbacks that come with producing figures with ggplot2. The primary difficulty is the syntax is inobvious without having read Wickham’s book (or the Wilkinson book that inspired it). Additionally there is an unfortunate dearth of documentation on the finer points of package.

Like many attempts to simplify tricky topics, the simplification adds its own baggage that confounds its initial objective. However, ggplot2 is immensely powerful and for most applications it is the best option available, I recommend it, but be sure to devote some time to learning it.

In this post I want to walk you through how to make a watermarked plot. Sometimes a bit of background information can keep a viewer in tune with the message of the figure.

A Cut to the Chase

One key frustration I experienced was the overly-pedantic omission of dual axis plotting. Granted there are many work arounds to this problem and with a little digging you’re likely to find Wickham’s work around, which exposes the tender underbelly of the package. This workaround showed me just enough of the inner workings of the package to be able to meet my client’s demands for a three-panelled plot with a watermark (things that aren’t available through the surface user interface of ggplot2.) I’d like to show you how you to do it.

The Setup

First lets get the packages we need installed and loaded:

install.packages(c("ggplot2", "grid", "gtable"))library(ggplot2)

library(grid)

library(gtable)The second and third packages are probably new to you so I’ll spend a paragraph to explain what they’re all about.

Wickham’s ggplot2 package was built on the pre-existing infrastructure of grid graphics. Grid is a low level plotting interface that suspends the user above the gory details of specifying an image tuple1 by tuple, but not so far as to lose any power. Grid-like plotting may be familiar to you if you have ever programmed graphics from scratch in a lower level language than R. The grid objects (grobs) produced by ggplot2 are hopelessly complicated and innacessible for direct manipulation. However, the package gtable exists to help us bridge the divide. So we use gtable to convert a ggplot2 image into a table of grobs, from this table we extract just the peices we want so that we can manually add them to our plots later using the grid package directly.

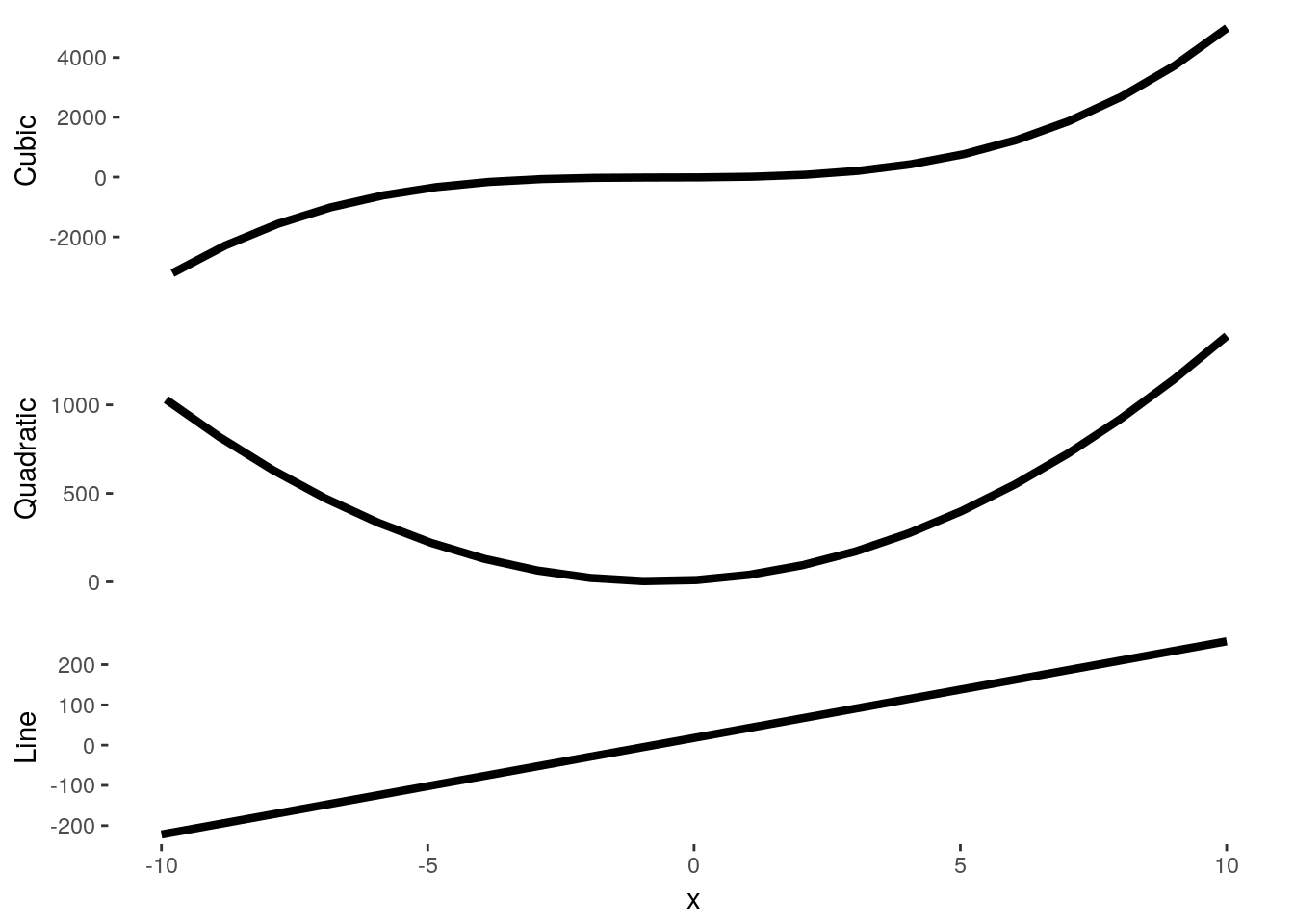

Back to the task at hand. We’re going to need some data for our plots. Lets make a quartic and look at its first three derivatives. We’ll use the original function as a watermark to compare the derivatives

x <- -10:10

y4 <- x^4 + 3*x^3 + 5*x^2 - 10*x

y3 <- 4*x^3 + 9*x^2 + 10*x - 10

y2 <- 12*x^2 + 18*x + 10

y1 <- 24*x + 18

polyData <- data.frame(x, y4, y3, y2, y1)Getting the Watermark

To pull out our watermark line, we first have to put it in a plot

quartPlot <- ggplot(data = polyData, aes(x = x, y = y4)) + geom_line(colour = "grey80", alpha = .75, size = 1)Now we build our gtable from quartPlot. The structure of a gtable is hopelessly complicated so ignore this if you’re not in the mood for some head scratching. What I didn’t borrow straight from Wickham I gleaned through agonizing trial and error. So by searching through the “grob” element of your gtable for the element that matches up with the “name” element “panel”, we can find the plotting panel where our line lives. The panel grob has 3 children, some gridlines, backgrounds, and our line. The line turned out to be child number 2.

grobTab <- ggplot_gtable(ggplot_build(quartPlot))

quartLine <- grobTab$grob[[which(grobTab$layout$name == "panel")]]$children[[2]]So now we have our watermark line ready to be added to our future plots.

The other plots

The other plots are going to need special themes to ensure the watermark is visible. Themes are how ggplot2 controls the final look of a plot. By specifying the background of both the panel and plot windows as “element_blank()” you ensure that your plots cover your watermark (this took me far too long to figure out, I had the watermark superimposed but highly transparent because I had given up on having it in the background.) I also removed the grid lines because they’re obtrusive2.

basePlot <- ggplot(data = polyData, aes(x = x)) +

theme(panel.background = element_blank(),

plot.background = element_blank(),

panel.grid = element_blank())

cubicPlot <- basePlot + geom_line(aes(y = y3), size = 1.5) + ylab("Cubic") +

theme(axis.title.x = element_blank(),

axis.ticks.x = element_blank(),

axis.text.x = element_blank())

quadPlot <- basePlot + geom_line(aes(y = y2), size = 1.5) + ylab("Quadratic") +

theme(axis.title.x = element_blank(),

axis.ticks.x = element_blank(),

axis.text.x = element_blank())

linePlot <- basePlot + geom_line(aes(y = y1), size = 1.5) + ylab("Line")Note that for the quadratic and cubic plots I also removed all traces of the x axis, so the plots can visually share the x-axis (although in reality they do not).

Setting up Viewports

A useful grid-ism to understand for working with ggplot2 is the concept of a viewport. Viewports are regions of the screen where things can be plotted. They’re specified as proportions of the screen for their width and height, with an x and y coordinates for the middle of the viewport. I could explain further but it will be quicker to show them in action

vp1 <- viewport(width = 1, height = .33, y = 1/6, x = 1/2)

vp2 <- viewport(width = 1, height = .33, y = 3/6, x = 1/2)

vp3 <- viewport(width = 1, height = .33, y = 5/6, x = 1/2)This code creates three viewports each occupying a third of the screen vertically.

We also need a viewport for our watermark but this takes some trial and error to fit well

quartLine$vp <- viewport(width = .8, height = .91, x = .55, y = .55)The Final Product

grid.newpage()

grid.draw(quartLine)

print(linePlot, vp = vp1)

print(quadPlot, vp = vp2)

print(cubicPlot, vp = vp3)

And voila, there you have a plot with a watermark to show off, there are lots of ways to customize these points, for my contract I included axis lines like so

grid.newpage()

grid.draw(quartLine)

print(linePlot + theme(axis.line = element_line(colour = "black")), vp = vp1)

print(quadPlot + theme(axis.line = element_line(colour = "black")), vp = vp2)

print(cubicPlot + theme(axis.line = element_line(colour = "black")), vp = vp3)For highly technical work it is important to note that the panels will not necessarily be in alignment. For example, because the longest axis label on the cubic plot is a digit longer than the other plots it’s drawing panel (where the plotting happens) is one digit narrower. This can probably be circumvent (though I’ve never tried) by manually specifying the size of the label box in your themes.

Outro

So there is how you can get around some of the limitations of ggplot2 to make really nifty figures for your own work and analyses. If you’re really intrigued, maybe investigate grid more deeply and shed the overhead of ggplot2, or you can delve deeper in how to combine the two to make a tricked-out personalized ggplot2 workflow to make some astonishing figures.

I hope you enjoyed this little journey through the innards of ggplot2.

-Chris

If you’re not familiar with the term tuple it’s a very useful term for vectors of coordinates or quantities. I wish I had learned it earlier in life. From high-school onward we’re used to specifying cartesian coordinates like (x,y). This bracketed construct of coordinates form a couple that represents a location in 2D space. When drawing an image we might want to tell our computers to draw a point at (x,y) and give it colour c, we can specify this as a triple (x,y,c). Adding two more quantities would give us a quintuple. By now you’ve noticed the pattern. This extends to as many quantities as you’d like, the genotype of an individual at many loci could be treated as an n-tuple.↩

I haven’t gone back to check yet, but I think if you set all the panel elements to “element_blank()” in the plot we used for the watermark you can ensure that you only have one child in your panel. This would make life easier because you wouldn’t have to search for which child is the line, you could just take element one every time.↩